Forced placement

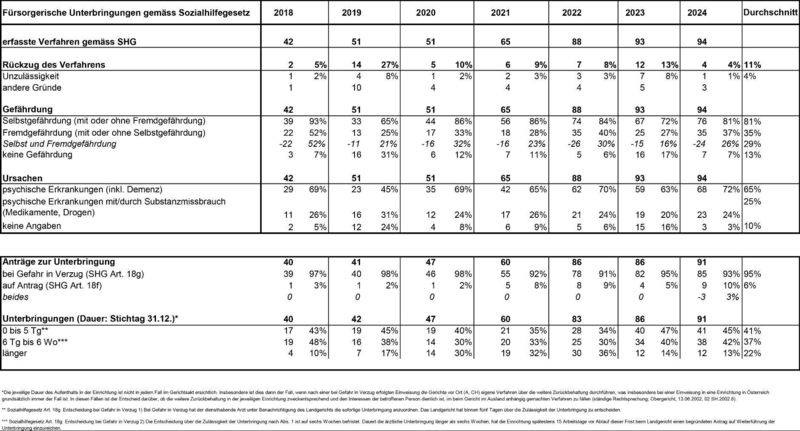

Custodial placements (involuntary committal) are very sensitive procedures in terms of human rights and can massively encroach on the individual's rights to freedom. They must therefore be carried out with care and restraint. The revision of the Social Welfare Act has introduced significant improvements to the procedure since 2021. The annual judicial care reports show that the number of involuntary placements has increased significantly in recent years. While there were still 42 proceedings for involuntary placement at the district court in 2018, there were already 65 in 2021 and 94 in the reporting year.

Admissions in acute cases

According to detailed statistics from the district court, 95% of all placement procedures between 2018 and 2024 were ordered by a doctor on duty in cases of imminent danger. A doctor on duty within the meaning of the legal provision is any doctor with a professional license in Liechtenstein. He or she is not necessarily qualified to assess the situation. Therefore, the establishment of a psychological emergency service or the introduction of a qualification, counseling or support system for the medical profession in psychological emergencies remains an essential human rights concern in order to prevent unnecessary admissions. By law, the court must decide on the admissibility of hospitalization within five days in cases of imminent danger. The medical referral report serves as the basis for this. The court's confirmation of the admissibility of the placement in the event of imminent danger is limited to six weeks. 4 percent of all placements were classified as inadmissible by the court.

Establish a psychological emergency service or introduce a qualification, advice or support system for doctors in psychological emergencies.

Review of the placement

According to the Social Assistance Act, retention must always be appropriate and in the interests of the person concerned. A transparent and regular review of the measures is mandatory. No later than six months after the start of the placement, the district court reviews whether the conditions are still met, based on reports from the clinic, independent expert opinions and hearings with the person concerned. The person concerned can apply to be released at any time, and a decision will be made in writing without delay. The district court's detailed statistics on involuntary placements between 2018 and 2024 show that 41% of involuntary placements ended after five days. 37% of placements lasted between 6 days and 6 weeks. 22% of placements lasted longer than 6 weeks.

Causes of placement

The Social Welfare Act defines the conditions for involuntary placement and stipulates that the order for involuntary placement is restrictive and primarily intended to prevent self-harm, and that an order to protect against harm to others can only be made if this "seriously and significantly endangers the life or health of others". As the detailed analysis of the statistics shows, an average of 81% of all proceedings since 2018 have been based on self-endangerment. Threat to others was the reason for 35% of all proceedings initiated during this period. In 29% of cases, there was both self-endangerment and danger to others. In an average of 12% of the proceedings initiated, there was neither self-endangerment nor danger to others. Accordingly, no proceedings were initiated in these cases, the proceedings were discontinued due to inadmissibility or a voluntary admission took place.

During the period under review, 65% of the reasons for involuntary committal were psychological or mental illnesses with partly physical causes (including dementia) and 25% were mental illnesses in combination with or triggered by substance abuse. severe neglect, as permitted by the Social Welfare Act, was not given as a reason for committal in any case. In 10 percent of cases, no cause is known.

The problem of accommodation abroad

Practically all placements are made in foreign, mostly Austrian or Swiss facilities. The Committee under the UN Convention against Torture (CAT) expressed concerns about this in its recent 2024 report on Liechtenstein. It sees difficulties for Liechtenstein in monitoring placements, granting visits and assuming responsibility in the event of allegations of torture and recommends that corresponding capacities be created domestically.

It is more difficult to monitor placements in foreign facilities, as the supervisory bodies of the respective countries are responsible. Among other things, the respective duration of the stay is not always evident from the court file in Vaduz. This is particularly the case if the local courts conduct their own proceedings regarding further retention. This is always the case in Austria. For psychiatric admissions to Swiss psychiatric or welfare facilities, the VMR has been recommending the conclusion of negotiations on a corresponding state treaty for several years. At the end of 2019, the first draft of the treaty was submitted by Liechtenstein to the Federal Office of Justice. According to the Liechtenstein representation in the negotiating delegation, there was another regular intergovernmental exchange on the planned treaty in 2024. The text was largely finalized, with only a few details remaining at the end of the year. The aim is still to conclude the negotiations quickly, if possible in 2025.